⬆︎ Throat Singing Styles ⬆︎ (click to listen)

The Tiny Republic of Tuva is a giant when it comes to mastery of the human voice. Tuvan throat singers can produce two or three, sometimes even four pitches simultaneously. The effect has been compared to that of a bagpipe. The singer starts with a low drone. Then, by subtle manipulations of his vocal tract and keen listening, he breaks up the sound, amplifying one or more overtones enough so that they can be heard as additional pitches while the drone continues at a lower volume. Despite what the term might suggest, throat singing does not strain the singer's throat.

The Ancient Tradition of throat singing (xöömei in the Tuvan language) developed among the nomadic herdsmen of Inner Asia, people who lived in yurts, rode horses, raised yaks, sheep and camels, and had a close spiritual relationship with nature. Throat singing traditionally was done outdoors, and only recently was brought into the concert hall. Singers use their voices to mimic and interact with the sounds of the natural world—whistling birds, bubbling streams, blowing wind, or the deep growl of a camel. Throat singing is most commonly done by men. Although custom and superstition have discouraged women from throat singing, recently this taboo is breaking down, and there are now excellent female throat singers too.

A Unique Concept of Sound. The Tuvan way of making music is based on appreciation of complex sounds with multiple layers or textures. To the Tuvan ear, a perfectly pure tone is not as interesting as a sound which contains hums, buzzes, or extra pitches that coexist with the main note being sung. Tuvan instruments are designed and played to produce such multi-textured sounds as well.

(sigit)

[suh-gut]

(khoomei, hoomei)

[her-may]

(kargiraa)

[kar-guh-rah]

(borbannadir)

[bor-bong-nah-dur]

(ezengileer)

[eh-zen-ghi-lair]

VIDEO: The xöömei, sygyt, and kargyraa styles explained and demonstrated by members of Alash.

NOTE: The term xöömei refers to a particular style but also to throat singing in general. It is sometimes spelled khoomei, hoomei, or choomeij.

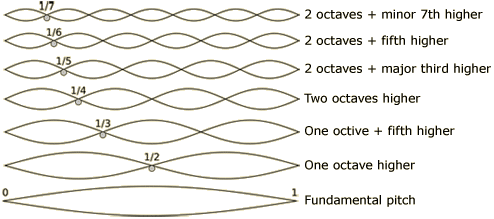

What Are Overtones? When a string or a column of air vibrates to produce sound, the pitch that we hear is determined by the length of the string or air column and how fast it vibrates (its frequency). But the pattern of vibration is not simple. The entire length of the string or air column, vibrating as a single segment, produces what we call the fundamental frequency, the frequency that is clearly audible and gives the tone its pitch. But at the same time, smaller segments (halves, thirds, fourths, etc.) of the string or air column are vibrating faster than the fundamental frequency. The smaller the segment, the faster it vibrates. For example, each half of a string will vibrate twice as fast as the entire string, and each third of the string will vibrate three times as fast as the entire string. We rarely hear these higher frequencies as distinct pitches because they have less power than the fundamental frequency. But in combination, these smaller vibrations determine the timbre or quality of the sound. The pitches associated with these higher frequencies are called overtones, harmonics, or partials. This diagram shows how the frequencies of successively smaller segments of a string relate to the pitches of the overtone series:

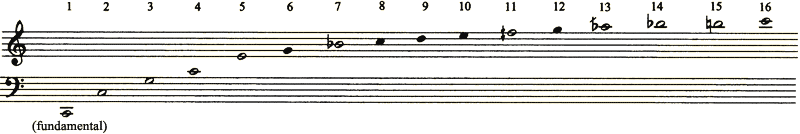

First sixteen pitches of the overtone series (harmonic series) for C

How to Listen. The overtones heard most prominently in Tuvan throat singing are indicated in black on the musical staff. These are the high fluty whistles which a singer can manipulate to form a melody floating high above the low drone pitch. (Notice they form a pentatonic scale.) Try listening for the more subtle overtones in the range of 2 through 5 in the series. While the western listener may want to identify which overtones become distinctly audible, the Tuvan listener enjoys the entire array of pitches, hums and buzzes as aspects of one sound, like facets of a diamond. To listen in this way, a newcomer to throat singing is advised to listen to the low drone, then bring the middle into focus, then hear the entire surrounding sound.

Cowboys of the East. In Tuvan songs, the complex textures of xöömei often alternate with a simpler melodic use of the voice. Just as western cowboys play guitar or banjo, Tuvan cowboys often accompany themselves with stringed instruments, either plucked or bowed. Many songs are performed to the rhythms of horses trotting or cantering across the open land, and instruments often are decorated with carved horses' heads.

Bady-Dorzhu Ondar playing the doshpuluur in Tuva (photo by Wada Fumiko, 2019)

Throat Singing Reaches the West. For most of the 20th century, Tuva was isolated from the rest of the world by its remote location (map) and Soviet-era travel restrictions. That began to change in the 1980s, when the Nobel Laureate physicist Richard Feynman and his friend Ralph Leighton set out on a quest to visit Tuva, a country which for years was known to the West only for its unusual triangular stamps. Feynman and Leighton became early fans of throat-singing and brought it to the attention of Europeans and Americans. American ethnomusicologist Ted Levin travelled to Tuva in the late 1980s and brought the group Huun-Huur-Tu to the United States. Throat singing gained a wider western audience with the release of the Academy Award nominated film, Genghis Blues. The film documents the musical journey of the blind American bluesman Paul Pena, who heard Tuvan throat-singing on a short-wave Russian broadcast, taught himself to throat-sing, and traveled to Tuva to take part in a music festival.

Today Tuvan musical groups such as Huun-Huur-Tu, Alash, Chirgilchin, and Tyva Kyzy regularly tour internationally as well as throughout Russia. Music festivals and throat-singing competitions draw hundreds of international musicians and fans to Tuva each summer. Tuvan musicians, scholars, and organizations such as universities and the Tuvan Cultural Center are working to preserve the country's unique musical heritage and to encourage young singers to keep it alive.

Suggested Reading:

Deep in the Heart of Tuva: Cowboy Music from the Wild East by Ralph Leighton (Musical Expedition series, Ellipsis Arts, 1996), a delightful introduction to Tuvan culture and music. Includes CD.

Tuva or Bust! by Ralph Leighton (W.W. Norton & Co., 2000), an entertaining account of physicist Richard Feynman's quest to travel to Tuva.

Where Rivers and Mountains Sing: Sound, Music, and Nomadism in Tuva and Beyond by Theodore Levin with Valentina Suzukei (Indiana University Press, 2006), a readable and thorough account of Tuvan music and culture. Includes CD/DVD.

Xöömei

Xöömei Sygyt

Sygyt Kargyraa

Kargyraa Ezenggileer

Ezenggileer Borbangnadyr

Borbangnadyr